A Return To The Hallow

Dusting off a hymnal, following the Shepherd, and finding a song already in progress

I woke with my head still thick from last night’s Benadryl—the kind of fog that follows a mind spun out on sugar and then forced to be still. Charles had already set a cup of coffee by the bed, as he kindly does every morning. I slipped into the cloud chair in the corner and let the quiet hold me for a moment, hoping the house would stay hushed long enough for the soul to catch up. The last two days had been a slow ease back into music—testing ideas with online tools, remembering what it feels like to shape sound the way I once shaped private prayers. I asked Charles to grab the United Methodist Hymnal he’d found at Goodwill a couple years back for a dollar. I wanted to sit with something older than me—older than microphones and platforms and all the little measures we keep of what “works.” I wanted to learn again from what the saints sang before us, and to let Scripture—not algorithms—set the key.

Part of the impulse was practical. I’ve grown weary of episodes being flagged whenever my studies lean on copyrighted tracks. But the deeper reason was hunger. If hymns have carried the Word across centuries, then perhaps listening carefully—how they’re constructed, where they root, what they confess—might help me shape something faithful and true, something new that is still recognizably the Lord’s.

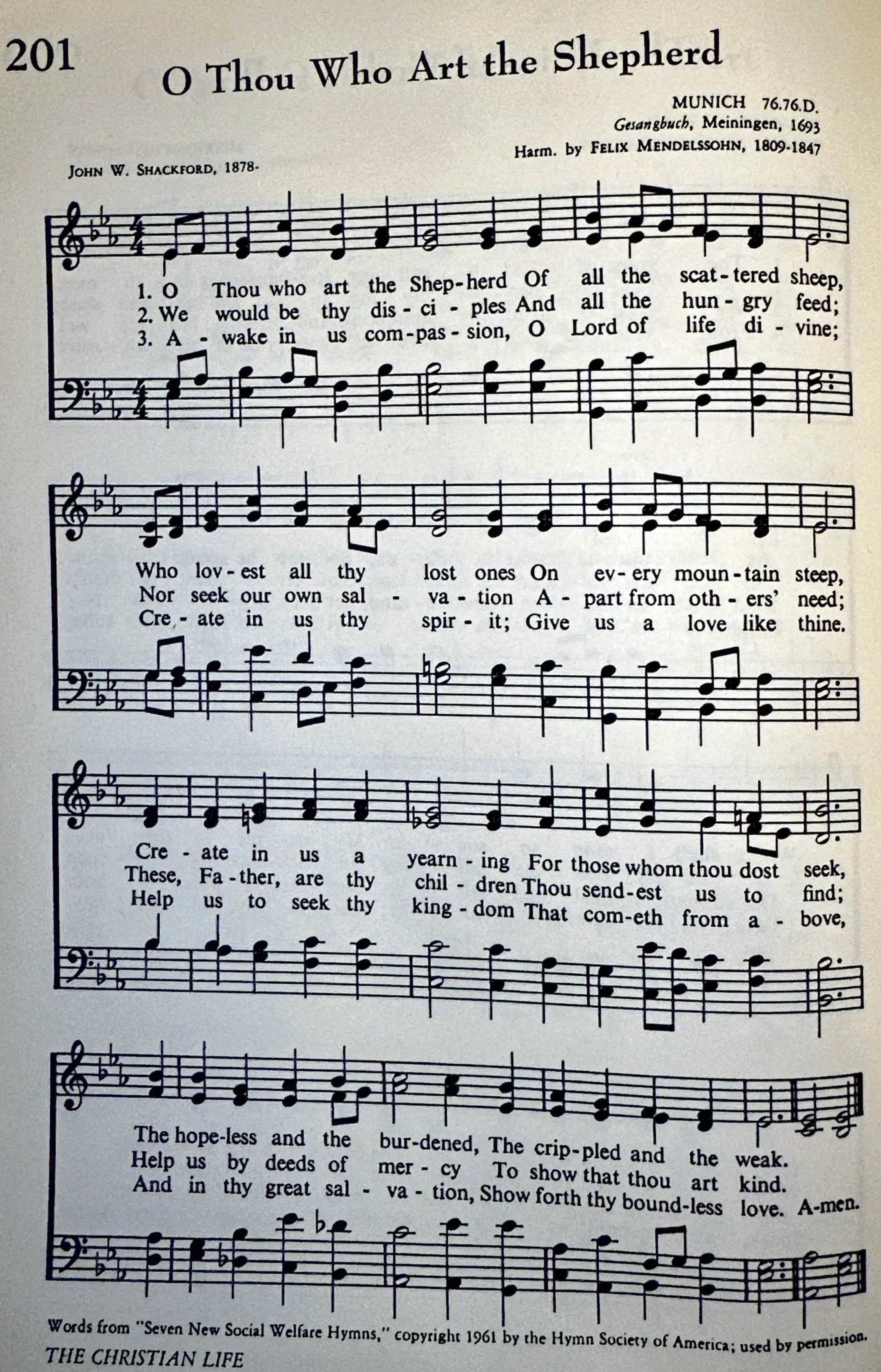

I opened the hymnal without aiming and landed on Hymn 201: “O Thou Who Art the Shepherd.” The page was simple: tune name MUNICH (76.76.D), origins in a 1693 German Gesangbuch from Meiningen, with a later harmonization by Felix Mendelssohn near the end of his life (1847). The text was by John W. Shackford (1878), a Methodist minister whose pen tended toward the Church’s call to mercy. Decades later, the Hymn Society included it in a small 1961 collection, Seven New Social Welfare Hymns—a quiet way of saying this wasn’t written merely for cozy devotion; it was written to shape hands and feet.

The hymn is found as hymn #201 in “The Methodist Hymnal” (1966) and is also part of "Seven New Social Welfare Hymns".

I traced the melody with my eyes and felt the way it leaps on “Shep-herd”—a clear ascent to the tonic, as if the line itself must rise to name Him—and then descends in calm steps on “scattered sheep,” like a careful walk down into the valley to find the one who wandered. Mendelssohn’s harmonies breathe with the tenderness of someone kneeling at another’s side. Nothing flashy. Nothing that draws the ear away from the text. Just a steady arm around a tired shoulder.

What held me wasn’t nostalgia. It was recognition. The language and the line carried Scripture in their bones—not pasted in, but pulsing beneath the surface. I could hear Psalm 23 move through the phrases:

“The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want.

He makes me lie down in green pastures.

He leads me beside still waters.

He restores my soul.

He leads me in paths of righteousness for his name’s sake.” (Psalm 23:1–3, ESV)

I could hear Ezekiel 34, where the Lord Himself steps forward as Israel’s shepherd:

“I myself will be the shepherd of my sheep, and I myself will make them lie down, declares the Lord God. I will seek the lost, and I will bring back the strayed, and I will bind up the injured, and I will strengthen the weak.” (Ezekiel 34:15–16, ESV)

And I could hear the parable of the lost sheep spilling into the margins:

“What man of you, having a hundred sheep, if he has lost one of them, does not leave the ninety-nine in the open country, and go after the one that is lost, until he finds it? And when he has found it, he lays it on his shoulders, rejoicing.” (Luke 15:4–5, ESV)

The hymn felt like Scripture remembered aloud—not just the comfort of being found, but the formation that follows. Shackford’s recurring prayer (the doxology after each stanza) asks the Lord to create in us a yearning for the ones He seeks: “the hopeless and the burdened, the crippled and the weak.” That little line carries the weight of Matthew 25 and the fragrance of Isaiah 61—the anointed One binding up the brokenhearted, proclaiming good news to the poor. The Greek term the Gospels often use for Jesus’ compassion—splagchnízomai—speaks of an inward, gut-level movement; and the Old Testament’s covenant love—ḥesed—names the faithful, steadfast mercy that refuses to let go. Shackford’s hymn quietly calls us into both: not sentiment, but Christ-shaped love.

And there, unannounced, I felt a familiar tension: I have served on worship teams; I know how to carry a room. Public expression often comes easier than private prayer. Recently I’ve had to admit that, and the admission has not been condemnation but clarity—a mercy of its own. The Shepherd does not only gather me into His fold; He teaches me to walk with Him toward the ones still scattered on the steep places.

I sat with the hymn a long time and then began to answer it. Not to replace or modernize, but to echo. I opened a notebook and, with a little help from online tools, began to shape a fresh prayer in the same meter—a quiet, contemporary language that could sing on the wind without losing the heart of Shackford’s plea. When the words finally rested into place, I gave the song a body—key, tempo, a sound that could breathe at a walking pace. G major. Sixty-eight beats per minute. Nylon guitar felt right—round, pastoral. Rhodes could glow like early light. A cello might hold the silence the way valleys hold fog. And a simple stack of female harmonies—soft at first, then luminous—could lift the doxology without ever drawing attention away from the Shepherd Himself. I asked for no drums, no rush, nothing that would make the feet run. Just a steady gait, because the One who seeks does not panic. He searches deliberately.

When the track rendered and I pressed play, I didn’t analyze it. I listened. The first chord opened like a sunrise slipping over pines. The guitar breathed in gentle patterns, letting open strings drone a little like a shepherd’s pipe. One voice entered, then two, then the quiet choir that happens when harmonies lie close and true. On the doxology the cello swelled—not to steal the moment, but to place a hand at the small of the back and help the prayer stand. And on the last four measures, where the text pleads, “Show forth Thy boundless love,” everything lifted and then let go—reverberation fading into wind, and somewhere behind that, the faint, happy clatter of bells you almost have to imagine to hear.

I didn’t plan to cry. But it felt like the Spirit was singing something back.

I’ve newly learned that hymns are inheritance. To open a hymnal is to enter a prayer already in progress. The tune MUNICH has been sung by believers who planted wheat and buried their dead in centuries I’ll never touch. Mendelssohn gave those notes a quiet tenderness near his own end. Shackford set the Church’s face toward the hungry and the weak. And we—so far downstream from those days—are given the mercy of remembering what they remembered. David’s shepherd-king becomes Christ the Good Shepherd; the valley of the shadow has a Companion now, who lays down His life for the sheep (John 10:11). The pattern is not subtle: God seeks; God finds; God carries; God forms a people who do likewise.

It has always been this way. The Lord maintains the boundaries of His name by going after what is His. When Israel’s shepherds failed, He Himself stepped in and said, “I will set up over them one shepherd, my servant David, and he shall feed them” (Ezekiel 34:23, ESV). In Christ, that promise arrives—not merely as comfort, but as commission. Peter tells the elders to shepherd the flock of God, not domineering but being examples (1 Peter 5:2–3), and then names Jesus the chief Shepherd who will appear (1 Peter 5:4). Hebrews blesses us with a benediction to “the God of peace who brought again from the dead our Lord Jesus, the great shepherd of the sheep,” the One who equips us with everything good to do His will (Hebrews 13:20–21). The theme keeps circling back: we are not only found; we are sent. The Shepherd’s care becomes the Shepherd’s call.

There is a reason this particular hymn found its way into a small mid-century collection aimed at the Church’s works of mercy. Shackford’s lines refuse to let salvation become private property. “We would be Thy disciples / And all the hungry feed; / Nor seek our own salvation / Apart from others’ need.” That’s Matthew 25 without quotation marks—Christ recognized in the least of these. But the hymn never lets mercy untether itself from the gospel. It asks first for new hearts—“Create in us Thy Spirit, give us a love like Thine.” The order matters. Deeds that are not born of regenerate affection can perform for a while but will eventually burn out or bend inward. The Shepherd’s love remakes us; then we walk.

Sometimes I think our lives are arias stitched together by the same refrain: return. Return from self-reliance to trust. Return from performance to prayer. Return from being preoccupied with the ninety-nine to looking up at the ridge and seeing, with Christ’s eyes, the one lamb that cannot find the path back. To return is to remember whose we are—and to remember that the One who calls us His has gone first, down into a darker valley than any of us will ever walk alone.

In the smallest way, that’s what happened in my living room with a thrift-store hymnal and a quiet morning. I didn’t set out to “rewrite” a hymn; I set out to sit under one, and to let the Word inside it move through me until a prayer of my own emerged in response. I’m convinced the Lord delights in that kind of work—not because our offerings are grand, but because they are given back. An old melody can carry a new confession; a new lyric can carry an old truth. The Shepherd wastes nothing. Even the hollows—geographic and personal—are His.

The song that came from that morning is called “Shepherd in the Hollow.” It is not a cover and not a clever exercise. It is a small gift returned: Scripture remembered, mercy requested, and a melody that knows how to walk. If you choose to listen, I pray you’ll hear what I heard—the voice behind the music. The One who leaves the ninety-nine. The One who binds up the injured and strengthens the weak. The One who names you and carries you home.

“Your rod and your staff, they comfort me.” (Psalm 23:4, ESV)

“He calls his own sheep by name and leads them out.” (John 10:3, ESV)

I don’t want to let the moment pass without saying this plainly: the Shepherd is not sentimental. He is holy and good. He does not wink at our wandering; He bears it on His own shoulders and pays for it with His blood. The cross is the cost of the parable’s joy. Grace is not a mood; it is a Person who laid down His life to make us His. That is why mercy can flow freely now—not as the price of admission, but as the fruit of belonging. We feed the hungry and seek the lost not to prove ourselves but because His life has taken root in us. Our compassion is not the root of salvation; it is the evidence that the Good Shepherd is near.

So, yes, I’m still learning to let private prayer lead public expression. I’m still being called from platform to pasture, from plans to presence. But in the quiet, I think I’m hearing the simple shape of discipleship again: hear, follow, carry. Hear His voice in the Word. Follow His steps into the steep places. Carry what He loves in the way He loves it. And when we grow tired—and we will—rest on the same shoulder that bore us home in the first place.

This is not nostalgia. It is now. The lost are still on the mountain. The hungry still wait. The weak still need carrying. And the Shepherd? He is still searching, still calling, still singing—sometimes through a nineteenth-century chorale, sometimes through a nylon guitar at sixty-eight beats per minute, sometimes through a trembling little prayer that feels like it arrived from somewhere older and kinder than we are.

If you’d like to sit with the hymn and with the song it inspired, I’ve placed the recording below. Linger as long as you like. Read Psalm 23 slowly. Let Luke 15 announce itself. And ask, as the hymn does, for a heart that yearns for those He seeks.

“Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life,

and I shall dwell in the house of the Lord forever.” (Psalm 23:6, ESV)

“Rejoice with me, for I have found my sheep that was lost.” (Luke 15:6, ESV)

When you’re ready to rise, you’ll still be in the valley—but you won’t be alone. And perhaps you will discover, as I did in a quiet room with a thrift-store hymnal, that the oldest songs can become the newest prayers, and that the Shepherd knows exactly how to find you in the hollow.